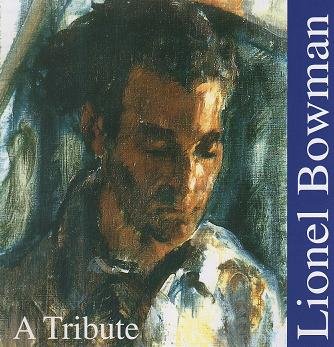

The below remarks are made by Cara Kelson and used in the Magic Touch by Wallace Tate website.

The below remarks were made by Cara Kelson (nee Hall ’47), at the book launch, February, 22, 2003 in Perth, Western Australia

Thank you Wallace, for asking me to speak about Lionel. It has been a real trip down memory lane for me, and I only hope I haven’t intruded myself too much in these remarks. But there were many things we were all experiencing, not just the musical life around us, but the increasingly difficult times we were living in. This was 1938.

I had arrived in London from New Zealand, ready to start at the Royal Academy of Music in September. Looking back now, I am reminded of what a marvelous age it was for pianists. In those early months, I heard people like Schanbel, Moiseiwitsch, Solomon, Egon Petri, and Rachmaninov. Myra Hess and many others. But there were also many young artists emerging from the Royal Schools and other places.

Almost at once, I met Lionel among the students in Vivian Langrish’e studio. Lionel was 19, well into his academy training, and he took me, a 16-year-old newcomer – under his wing. Indeed, he became something like a big brother to me. There was, of course, the Commonwealth bond between us.

Professor Langrish (Viv behind his back) brought all his students together regularly, at the practice concert held at his home in Primrose Hill. One’s first practice concert was something of an ordeal, but after that, general camaraderie prevailed with real enjoyment of our music-making together. After playing at a practice concert one could then perform that work at Duke’s Hall

Among all the talented Langrish students, Lionel was outstanding. What I remember most was the brilliance of his technique (he had Horowitz – like fingers) that was coupled with interpretations of deep understanding. His music could dazzle, but it was always satisfying. (I should mention that all the Langrish students had a beautiful singing tone).

In himself, Lionel was full of fun, and very helpful in every way, but when it came to music, he was always very serious. Coming from far away we were often hearing great music for the very first time. Years later when discussing this, Lionel almost shivered at recalling the effect it had on him of hearing the Brahms B flat concerto for the very first time. (I had lots of similar memories, too).

All students were encouraged to sit in on the orchestral rehearsals with Sir Henry Wood, but we could also get free tickets for the orchestra rehearsals at Queen’s Hall of the BBC and other orchestras, and it was of great interest to hear and see all the leading conductors of the day at work. Lionel had joined the R.A.M’s conductor’s course at the urging of Benjamin Dale the Warden, a class of six run by Ernest Read who also taught aural training. He had to become acquainted with various orchestra instruments and studied the cello with Cedric Sharp, French horn with Aubrey Brain (whose young son Dennis was already an outstanding Academy student), and the clarinet with Reginald Kell. He also had singing lessons.

I never saw Lionel in action on the podium conducting the Academy’s Third orchestra, though I do remember one occasion when a nervous young student stood as stiff as a one-armed bandit while Sir Henry Wood tried in vain to get him to use his left arm! Years later Lionel told me with amusement that his moment of triumph came when he played the triangle in the First orchestra at the R.A.M’s annual Queens Hall concert, Sir Henry Wood conducting. However, I do remember Professor Langrish’s comments about the way Lionel’s conducting experience helped to control his rhythmic sense and tempos, and to shape his phrasing, all of which showed up in his own playing.

But with all the excitement of London’s musical and theatrical life, and our own busy schedules of lessons, lectures, classes and performances, the thought of war hung over our heads – and war became a reality in September 1939 after Hitler’s armies invaded Poland. Immediately there was a cancellation of concerts, but when the bombs didn’t fall on London, most concerts were reinstated, though often changed to earlier times because of the blackout. Audiences returned and to bring cheer to as many Londoners as possible, Myra Hess inaugurated her wonderful lunchtime concerts at the National Gallery. They were to run right through the darkest years of the war, and into the peace, ending in 1946.

At the academy, we all continued our studies as intensely as before, with our schedules rearranged where possible to cur down on travel time. Then, in the spring of 1940, the German army moved swiftly, first with the invasion of Norway, followed by the low countries, all falling one by one. The little boats crossed over to Dunkirk to rescue the British Expeditionary Force and those soldiers began to pour out of Victoria Station out into the London streets.

The Academy authorities were urging those of us from overseas to think of returning home. Lionel, of course, was winding up his scholarship. In my case, I was told that my third and fourth scholarship years would be held over until after the war.

The last time that Lionel and I were in Queen’s Hall was in 1940 for the final concert of the academic year, with the R.A.M Orchestra conducted by Sir Henry Wood. The National Anthem, which opened the concert, was Sir Henry’s own arrangement, but this time he had the strings play each note on an individual down-bow which gave the Anthem great emotion and power. At the end, there was a slight pause, and then with a sudden movement of his baton, the orchestra burst into La Marseillaise. The atmosphere was palpable. France had fallen the day before. And it wouldn’t be long before our beautiful Queen’s hall would be reduced to a pile of rubble.

Soon after that final concert Lionel and I met at Duke’s Hall as we had both been recalled for Academy prizes. He was still the big brother with his encouragement and calm presence, standing with me before I went in to play. We were both successful in our sections – for him it was a triumphant end to his student days.

During his time at the Academy, Lionel had won the Matthew Fillmore and Rotter Prizes and was now awarded the prestigious and coveted Chappel Gold Medal. In years to come he would be made a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Music. And so we said our goodbyes and were both lucky to voyage back safely to our homelands – though my trip had its dangerous moments, an attack by a German submarine. (The Rangitiki was in the center of a convoy of 46; the tanker beside us was sunk.) Before the Rangitiki was halfway to Panama, the bombs were dropping on London. The Battle of Britain had begun.

I was back in London for VJ Day, and soon the word went around our old circle “Lionel is Back!” During the war years in South Africa Lionel had played with great acclaim in recitals all over the country (many were to raise funds for War Bonds), and as a concerto soloist in brilliant performances of the Liszt, Grieg, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky, including first performances in South Africa of Prokofiev’s Third piano concerto and de Falla’s Nights in the Gardens of Spain. Now, in post-war London, his career was to expand into an international one.

He was the consummate artist, a brilliant pianist with great sensitivity and integrity, soon to be engaged in a wide range of appearances, recitals, broadcasts, concertos, TV, touring in joint recitals with many international artists, spreading out to play in European countries, the USA and elsewhere. After the first post-war months, it was inevitable our meetings would be less frequent and that finally, our paths would diverge.

It would be some three decades later after I had moved to Perth with my American family, that we would meet again. I was excited to see one day, in a University of Western Australia program, that Professor Lionel Bowman of Stellenbosch University, South Africa, was coming to the University as Visiting Professor. You can imagine his surprise when I walked into the Callaway Auditorium and the pleasure we both had in picking up our friendship again. There was so much ground to cover! I was distressed to hear that his splendid concert career had to be curtailed because of the physical difficulties and injuries he had encountered with his small hands, – but it was inspiring to learn how it had turned him towards researching and analyzing, ever aspect of playing the piano, every moment that a pianist makes at the keyboard, and which finally molded him into a superb teacher.

I reminded him of something he told me so many years before. I’d played a recital program at the Langrish home, and afterward, Lionel (and he was the only one to do so) told me that one particular work I’d played was really too big for me. He said, “Strange… I could see the danger for you, but not for myself”.

He took me through the exercises he’d worked out, starting with the thumbs. I could immediately see the importance of concentrating, right at the beginning, of relaxing after every single note. (And incidentally, it was only a few days before I found that trilling had become much easier.) As Lionel said, “Sit very still. You prepare, play, finish. Drop the wrists. Test. Relax all the muscles”. And you continue to do the same with all th exercises that follow, — octaves, chords, scales, arpeggios. In this way, the muscles are being constantly released before muscular tension builds. Lionel emphasized, “You work at it until it is patterned into your subconscious and becomes instinctive, automatic”. He liked to remind one that relaxation means control.

Many people will do much of this naturally, but even great artists run into trouble – let alone young students. Look at Leon Fleisher and Gary Graffman, and more recently, my own countryman Michael Houston. Many people have written about how to play the piano, but no one has gone about explaining the best way to approach every movement one makes at the keyboard, as clearly as Lionel has done. He liked t say, “It’s all sensation which is difficult to put into words” – but Wallace has done a remarkable job in doing just that.

Lionel writes that he hopes pianists will find The Magic Touch both an inspiration and practical help on their musical journey. Congratulations Wallace! And thank you for all the work you have done to make this possible.