How Can the Bowman Piano Playing Method Help Me Play Better As a Classical Pianist?

By Marty A Cohn

Strictly speaking, the method that I want to explain below, can apply equally to pianists of all musical styles, but the Bowman method, which is the primary method I wish to write about has been created by a classical pianist who was experiencing many problems, due to muscular injury and tendonitis. I am including a brief history, to impress upon you the tremendous change that this style of playing can have on your ability to not only play, but also on the resulting sound.

It is almost inevitable that any serious pianist, who is practicing around seven hours a day, with complex musical scores, like the Brahms B Flat, or the Rachmaninov Concerto Number 3, is going to experience some degree of muscular problem in their career, as the time spent at the piano is time that the arms are supporting the hands, and the hands and wrists are regularly moving across the keyboard to play the notes. Now, while most of that is obvious, not so obvious is the state of play in the wrists, and hands.

Given that the keyboard spans multiple octaves, and the pianist normally remains seated on one spot on the piano stool, there is going to be a bit of movement, either from the hips to place the body closer to the section of the piano where the hands are meant to be, or there will be a case where the hands are not always at right angles to the piano. This is the first downfall for many pianists. While they are attempting to play across the keyboard, they will need to be sitting left or right, through the loosened movement of their hips, or otherwise, the strain that will come to the hand muscles will catch up at some point.

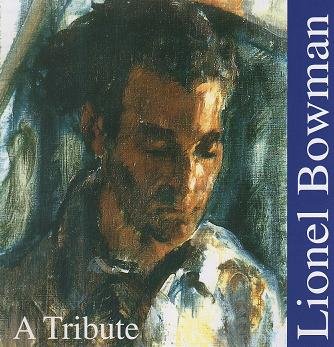

In the case of Professor Lionel Bowman, it was around his late thirties that the problem developed to a point where he could no longer play. For a serious or professional pianist, that can be a disastrous state of affairs, much like when a footballer needs to have a knee reconstruction. They would be out of the game for the best part of a season. In Lionel's case, it was several months at the least away from the piano.

Naturally, it is far better to avoid a playing style that will lead to this problem in the first place, so it is best to do something about it sooner, rather than later. This is where it becomes a good idea to adopt a new playing technique. In the case of Professor Bowman, the technique evolved out of necessity, sometimes the best teacher. He took the time to really study the anatomy, and realised that he had to modify his style of playing, as the body's anatomical design is not directly compatible with playing the piano. Essentially, part of the problem was the issue of muscle tone, but also, a large part was the problem with the relative angle of the keyboard, needing to be at right angles to the hand at all times. (or at least, as often as possible).

He also found that by strengthening the muscles in the fingers, he was able to deliver the power to play at higher volumes from the fingers, rather than use alternative muscles that allowed the possibility of other muscular injury. He also found the best way to condition his fingers was by practicing on a flat, wooden surface, which required more force to develop the volume required to hear the 'music'.

Whilst this all helped to a degree, there were still numerous exercises that he developed, to actually aid the spacing to grow a little larger between the ulna and radius bones of the forearm. Whilst the difference was subtle, it was the 'window' that allowed him to play more successfully, through the complex passages. He also had smaller hands, which again, made playing the piano more difficult. However, the bonus with his method was that he was able to overcome these seemingly impossible problems, and was able to relax more, and thus concentrate on producing a richer sound, that left him pain free.

That can only be a bonus for all pianists. The method is regarded as a little more complex at first, to get the hang of, but has been reported by many students to make learning, and playing new material easier, in the long run. One reason for this is that the mind subconsciously takes over, on some of the routines. It is rather like driving a regular route home. Have you ever arrived home, after a long day, and realised you did not actually remember the drive. You actually did so on a kind of auto pilot. The same can apply to this technique while playing, once mastered.

Are you interested in overcoming piano injury, for the long term?

You will also gain an enhanced comfort and improvement in your playing, with less stress and injury. To learn more, see the therapeutic techniques that are possible for classical pianists.